Kategorisierungen von Computerspielen gibt es meiner Ansicht nach so viele, wie es bestimmte Verwendungszwecke vorgeben: Das reicht von sehr persönlichen bzw. subjektiven Ordnungen (die leider häufig in die politische Diskussion einfliessen) bis zu ernsthaften Versuchen objektiver Taxonomien.

Eine Kategorisierung ähnelt insofern Theorien oder Methoden, als dass sich ihre Brauchbarkeit am jeweiligen Verwendungszweck messen lassen kann. Übliche Kategorisierungen richten sich meiner Ansicht hauptsächlich nach den marktüblichen Genres und den ’sichtbaren‘ Rahmenerzählungen, deren Bildern bzw. abgebildeten Handlungen.

Ich sehe darin zwei Probleme, für die ‚offiziellen‘ Kategorisierer und die, die diese Kategorien später als Werkzeuge anwenden:

Erstens: Eine strikte Kategorisierung qua Genre hat Probleme mit den zunehmenden Mischformen. Shooter enthalten heute z.B. häufig Adventure-Elemente. Multiplayer-Online-Rollenspiele sind meist sowohl taktische, Aufbau- als auch Gesellschaftsspiele. Sandbox-Spiele, in denen das Spielziel bzw. die Handlungsweisen nicht dezidiert vorgegeben sind (z.B. „Fable“, „Sims“) bzw. die anderer Genres ermöglichen, sowie emergierende, ’neue‘ Genres (z.B. ARGs) sind damit kaum bzw. nicht mehr ‚in Gänze‘ zu erfassen.

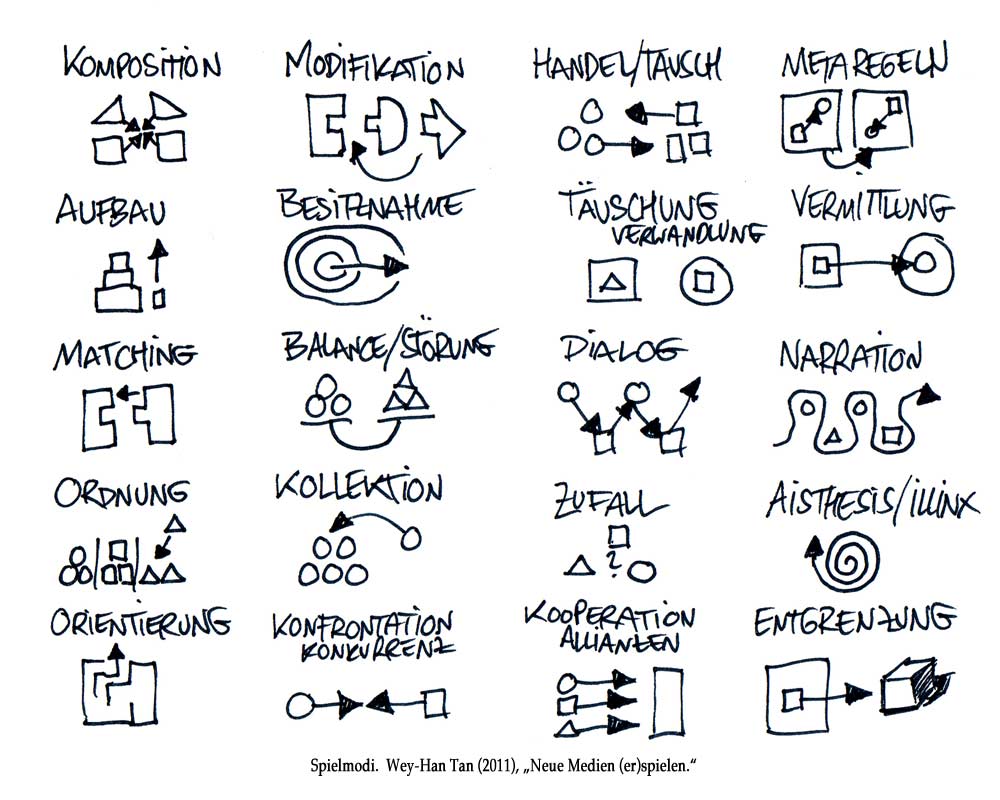

Zweitens: Wenn wir die Wirkungsweise bzw. Wirksamkeit von Spielen betrachten wollen, müssen wir – gerade weil es interaktive Medien sind – auch hinter die Bilder und Erzählungen schauen und die verschiedenen Spielmechanismen betrachten, denen sich der/die Spieler/in unterwerfen muss, um erfolgreich zu spielen bzw. überhaupt erst spielen zu können.

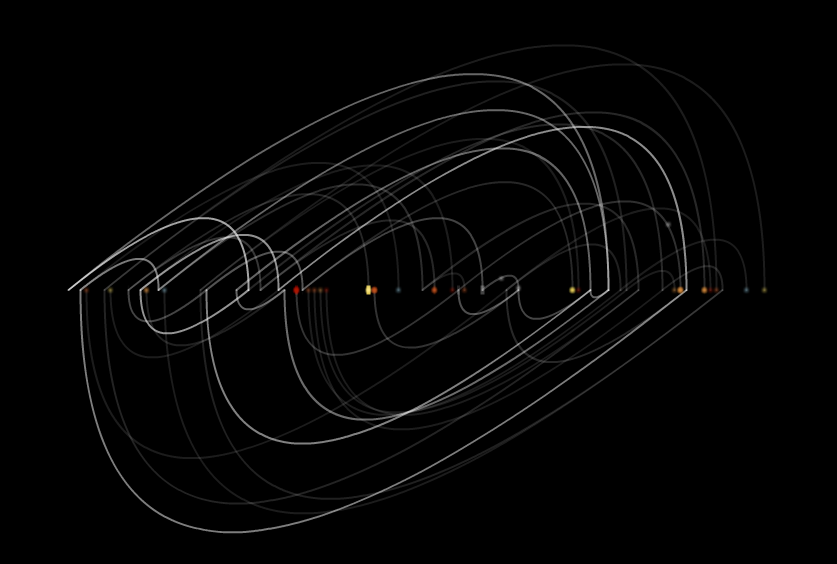

Unter der Oberfläche liegen die Grenzziehungen anders: First Person Shooter haben hier mehr mit Autorennspielen zu tun als mit Kriegssimulationen; Aufbausimulationen mehr mit Kriegssimulationen als mit kampfbetonten Multiplayer-Online-Rollenspielen; und die wiederum mehr mit klassischen Gesellschaftsspielen.

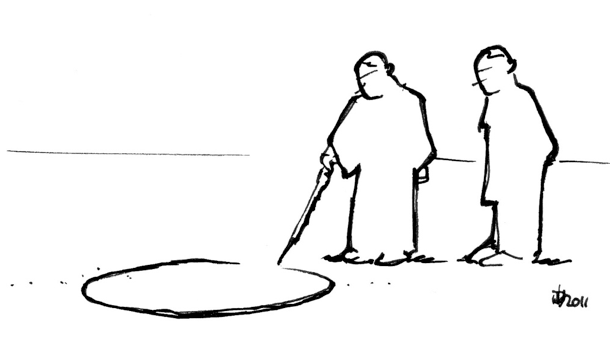

Claus Pias stellt folgende provokante These auf:

„Die Pädagogik argumentiert (wie mir scheint) auf einer einigermaßen dilettantischen Ebene, wenn sie glaubt, „Inhalte“ oder „Bilder“ seien der brisante Punkt an Computerspielen.“

Er begründet dies u.a. wie folgt am Beispiel von Strategie- bzw. Aufbauspielen:

„Man könnte den ganzen Markt der Strategiespiele anschließen: allüberall geht es um Verwaltungsakte, also um Bürokratien. Ob das nun eine Kleinfamilie, ein Pizzaservice, ein Themenpark, eine Bananenrepublik, eine Ameisenfarm, der Winter vor Stalingrad oder ein Arbeitslager ist, spielt auf dieser Ebene schlicht keine Rolle. Selbst bei der Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Schriften und ihren Empfehlungen für „hochwertige Software“ finden Sie keine geeigneten Kriterien, um im Spiel selbst (und nicht seinem Interface) irgendwelche pädagogischen Entscheidungen treffen zu können. Feinmotorik, Reaktionsvermögen, Konzentration, Problemlösen, logisches Denken, Motivation und Einübung des Umgangs mit Computern – all diese Fähigkeiten, die dort als pädagogisch wertvoll aufgelistet sind, kann man auch an den „bösesten“ Interfaces herausbilden.“

‚Äì Claus Pias (2001): „Computerspiele auf dem Prüfstand.“

Es geht also bei der Wirksamkeit von Computerspielen zumindest nicht nur um die Oberfläche, d.h. die sinngebenden Erzählungen und Bilder, sondern auch um deren narrative Strukturierung und die Spielmechanik. (Pias schlägt in „Computer Spiel Welten“ (2002) z.B. eine Kategorisierung in zeitkritische (Action-), entscheidungskritische (Adventure-) und konfigurationskritische (Strategie-) Spiele vor.)

Pädagogen benötigen also eine Möglichkeit, neben den narrativen auch die regulativen Aspekte von Computerspielen erfassen zu können. Möglichkeiten von Kategorisierungen dieser Art könnten z.B. über die Positionierung in einem Kontinuum lerntheoretischer Vorgaben erfolgen:

Welche Spiele erfordern und unterstützen reine Reiz-Reaktions-Verhalten bzw. reines Drill & Practice (Quiz, Action);

welche logisch-sequenzielles Vorgehen (Adventures, gerichtete Hypertexte, einfache Aufbauspiele);

welche systemisch-vernetztes Denken (komplexe Aufbau- und Strategiespiele, soziale Simulationen, Microwelten);

welche kommunikativ-soziale Kompetenzen (kollaborative Netzwerkspiele);

und welche metaspielerische Reflektion (atypische Spiele wie Frascas „September 12th“, LeDonnes „Super Columbine Massacre RPG“, Costikyans „Violence“, Shirts „Starpower“, die Produkte von Molleindustria oder Wiemkens „Breaking the Rules“)?

Aus medientheoretischer Sicht wäre z.B. eine Unterscheidungsebene über algorithmisch-hermetische Spiele (z.B. unvernetzte Konsolenspiele) und interpretativ-offene Spiele (digital unterstützte Kommunikationsspiele wie ARGs) aufgrund der unterschiedlichen Möglichkeiten – und Unmöglichkeiten – für den Spieler interessant.

Welche Kategorien wären noch denkbar, die interessierten Pädagogen neue Werkzeuge in die Hand geben?