One of mankinds greatest achievements is also one of its greatest obstacles in furthering the means to represent and thus reflect and understand ‚reality‘. Languages provides us with a seemingly simple way of assigning words to concepts to reality: Language, photographs, film, hypertext, games – all seem to be clear cut and distinguishable in their forms. All have a specific relationship to time and space in their acts of creation and those of reception.

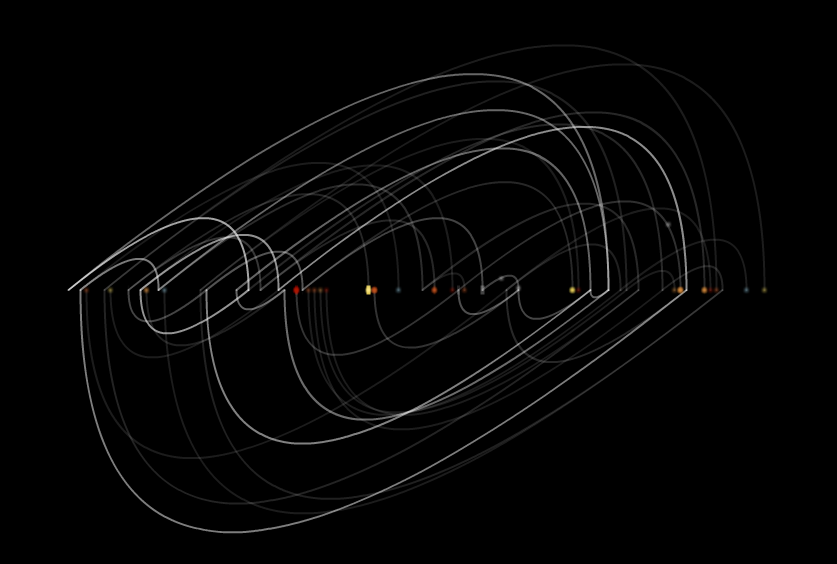

Language flows linearily, like a string of pearls coiling around the topic it tries to grasp, like the touches of a blind man trying to shape a sculpture out of thin air. Photography resembles an afterimage of a landscape illuminated by lightning, freezing a changing, moving world into one to behold in all it’s details, for once unchanging. Film moves our view like a puppet on a string, taking us relentlessly by the hand to follow what is laid out for us. Hypertext gives us some choice to choose between forking paths, maybe trace back and forth, like an idle or searching wanderer. And games – games provide us with language, images, moves, and choices, though it can not be found in these but in the rules that let us interpret them, interact with them. Games are what we turn into them by adding rules that differ from, yet resemble those given to us, ingrained in our identity and society.

Mercifully, the first rule of a game is: You don’t have to play, and if you want to play you do not have to accept the rules as they are. This could also be seen as the first rule of all media, of all medium, but is never as clear as in games – or as in arts.

One task suits both very well: Showing the limits and rules of media, of its beneficient and problematic potential, and that a word, a concept, a meaning, a rule system of production and reception, that these may may be altered by the artist, the game designer, the viewer, reader or player in an act of creation.